Illusion depends on directing the viewers attention to what the performer wants the viewer to see rather than what they need to see. When the trick is revealed the viewer having missed the important action due to the deliberate misdirection is amazed at the performers revelation. The latest Temasek annual report engages in this exact type of misdirection designed to focus attention away from the important points.

I must begin by emphasizing, as I always emphasize, that Temasek is only a piece of the whole puzzle. It is a major and important piece of the whole puzzle, but it is again only a piece of the whole puzzle. As I have already noted, even if everything Temasek claims about its returns is completely true, which is a dubious proposition at best, this does not in any way relieve the concern about the entirety of Singapore public finances.

The first basis for analysis is how an investor fared against the broader market. While Temasek is quite proud of its 8.86% total shareholder return between March 31 2012 and March 31 2013, this is less impressive than it appears. Over the same time period, the S&P 500 and FTSE returned 11.4% and 11.2% respectively. The Strait Times and the Hang Seng returned 9.9% and 8.5%. In other words, if Temasek only bought low cost exchange traded funds using the same geographic diversification strategy, they would have earned a slightly higher return of 9.2%.

As is repeatedly noted in finance research, there is no such thing as anyone who out performs the market for an extended period of time. In a way, a large institutional investor slightly underperforming the market by .4% is reassuring because it is what we expect in that they matched the market. This is the major concern about Temasek’s enormous claims about their long term returns: they do not match the underlying data of individual holdings or markets they were heavily invested in.

For 2013 anyway, congratulations Temasek: you slightly underperformed the market!

More important however, is the evolution of Singaporean finances. The Singaporean government is in many instances, such as with SMRT, simply subsidizing the profits that accrue to Temasek via their portfolio holdings. Consequently, while Temasek makes money, the Singapore governments loses money, and the two numbers come close to balancing out.

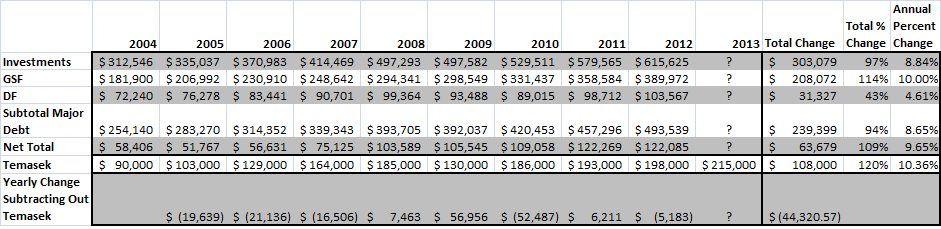

Here is a simple table below that I have prepared using data from the Singapore Ministry of Finance Budget website of assets and liabilities going back to the year ending March 31, 2004. It should be noted that to the best of my knowledge, the government has not posted a balance sheet for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2013 consequently I have not been able to calculate the change for the most recent year.

There are two things that should be focused on. First, while Singapore investments increased from $313 billion SGD to $616 billion SGD between March 31, 2004 and 2012 public debt was exploding at the same time. During the same period, major liabilities jumped from $254 billion SGD to $494 billion SGD. This resulted in growth in net assets from $58 billion SGD to $122 billion SGD for a total increase of only $64 billion. To frame this slightly differently, according to the Singapore Ministry of Finance, while publicly held investments increased by $303 billion SGD between 2004 and 2012, this occurred primarily from an additional $239 billion in new liabilities with only $64 billion SGD attributable to net asset growth. Put another way, Singapore has approximately four times as much public liabilities as net investments.

Second, incorporating Temasek into our analysis further complicates an already worrying result. If we take Temasek claims at face value that their portfolio value grew from $90 billion SGD in March 2004 to $215 billion SGD in 2013, this creates an enormous problem: if we subtract out the Temasek growth from Singaporean net asset growth over this time period, we have a negative number of $44 billion SGD. This implies that if everything Temasek claims is entirely true, then the rest of the Singapore, Inc. portfolio lost a significant amount of money.

When you make the comparisons year by year, the results are even more problematic. Let me give you an example. For the year ending March 31, 2009, suffering the effects of the global financial crisis Temasek understandably reported steep losses taking their portfolio from $185 billion SGD to $130 billion SGD. This is where it gets strange. The Singapore Ministry of Finance budget balance sheet for the same period reports investments and total debt essentially unchanged from the previous year. This means that while Temasek was reporting a $55 billion SGD loss, the rest of Singaporean investment portfolio would have had to have made a $57 billion SGD profit to offset Temasek losses.

To put this number in perspective, while the S&P 500, FTSE, and Strait Times were returning -37.2%, -33.1%, and -38.5% respectively, very close to the Temasek return of -29.7%, the rest of the Singapore investment portfolio must have returned an absolutely amazing 18.24%! In other words, the non-Temasek Singapore investment portfolio managed to outperform the Strait Times index by 56.77%. Now unless the Singapore Ministry of Finance magically maintained an enormous short position on global markets in 2008 and early 2009, it seems incredibly unlikely that they managed to pull off what would truly be one of the most amazing trades in the history of mankind to end up with no net change in total investment or net wealth.

Temasek’s returns are in line with the broader market. What continues to concern is its enormous deviation from the historical norm of market returns and the discrepancies within Singaporean public finances. These issues remain unresolved and quite worrying.

Follow me now on Twitter @BaldingsWorld

May I know some of the implications you were talking about?

Can you be a little more specific? What do you mean?

What I mean is:

1. the net asset you have in your analysis is quite small when compared to the GDP and the CPF liabilities.

what implication does that suggest?

2. the level of leverage is unbelievably high. May I know what is the source of that debt/nature of the debt?

also, does it collate well with the fact that the medical care fund we have work in such a way where only the interest is used, the big big principal they claim to deploy were never used. It resembles how madoff handles the charity monies he receive to help invest. he only pays the interests…

3. I also found it weird that the govt somehow have so much monies to buy all those expensive American fighter planes when its funds don’t have such a high return?

4. also, there is a plan to spend 14 billion of a 5 to 7 km tunnel which is incredibly expensive? why would the govt do that if it doesn’t really have that much net monies in the 1st place?

1. Given the amount of debt outstanding, Singapore is not as wealthy as it thinks. Still not bad, but not as wealthy as it thinks.

2. The two primary sources of listed liabilities on the government balance sheet are the Government Securities Fund used primarily, though not exclusively, by the CPF and the Development Fund. Development Fund borrowing is used to purchase “capitalizable assets” that the government can put down on the public balance sheet as an asset. Though I am speculating because there is no specific detail about this, the Development Fund borrowing is likely used for land reclamation type projects, and other similar type projects, which the government can then put the asset on its balance sheet.

3. There are a lot of things that don’t make sense about how the Singapore government manages its finances.

4. My guess would be that it is using Development Fund borrowing to invest in a tunnel that I would guess would be turned into a Toll Road which it could put on its balance sheet as an asset.

Hope that answers your questions.

no really.

I still doesn’t know how to realistically access if Singapore govt is really wealthy or just posing as wealthy.

I believe it is not entirely posing as wealthy but closer to posing than truly.

actually, I understand the mechanism you describe between the debt and asset. Question however:

1. are you suspicious at the super high value of the investment in the tunnel?

2. SHOULDN’T there be an incentive to look for a lower number to invest since that would push roe?

1. are you suspicious at the super high value of the investment in the tunnel?

Not sure to be honest as I am not qualified to judge the expected cost of construction projects. At the same time, I do know that those type of projects are incredibly expensive. A super high value for a tunnel in many ways is not surprising but I must re-emphasize that I am not an expert on costing out construction projects.

2. SHOULDN’T there be an incentive to look for a lower number to invest since that would push roe? Most people don’t pay attention to individual investments but only the final number for all investments like in Temasek. Lowering the cost of the tunnel by a small amount is not going to have a material impact on the investment success of the tunnel or the Temasek portfolio.

There is this following comment by a reader in TR Emeritus on your same article which is re-posted there:

============================

Moroose:

July 8, 2013 at 8:12 pm (Quote)

This is a horrible analysis drawn from erroneous figures and flawed logic.

Here’s why:

1. Using 31/3/2012 as an example, looking at the Singapore Government balance sheet (http://www.baldingsworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/06-Assets-and-Liabilities-for-2012.pdf) – link provided by the professor himself, one would notice that for unknown reasons, the professor decided not to include cash of S$150b (or about a fifth of total assets) in assets. Now, when an entity issues bonds, debentures, T-bills, or any other form of debt, they would typically get cash in return, which are then used for investment. Hence there’s no reason not to include cash.

2. For some apparent reason, the professor decided to classify Development Fund (DF) and Government Securities Fund (GSF) as debt. A quick check shows that while loans indeed comprise part of these funds, there are other items that are included. In other words, these funds do not make up government debt. Link as follows: (http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/aol/search/display/view.w3p;page=0;query=DocId%3A%2297e70a46-e779-4db6-ae40-300fdf9d0e08%22%20Status%3Ainforce%20Depth%3A0;rec=0)

(http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/aol/search/display/view.w3p;page=0;query=Id%3A%22c3b0d2ef-d978-4917-9b23-2311c07b0e7f%22%20Status%3Ainforce;rec=0)

3. Earlier, Steve Wu did some research on government debt (http://www.tremeritus.com/2012/12/05/a-physicist-looks-at-the-financial-governance-2/), and government debt for 31/12/2011 was S$354b (note that this figure is the same as provided by the department of statistics: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications_and_papers/reference/yearbook_2012/yos2012.pdf) as compared to the professor’s S$457b. Now, I admit that there would be some differences as the Department of Statistics provides figures as at 31/12/11 whereas the professor has used figures as at 31/3/12, but I think a S$103b difference in a 3-month gap is too far off.

4. Taking the above points into account, the government’s net asset for 31/3/12 should be S$765b – S$354b = S$411b as compared to the professor’s figure of S$122b (note that there would be some differences anyway due to the 3-month gap as mentioned in point 3). It should be reasonable to assume that the net assets for the other years are similarly in error. And since the figures are in error, that makes the rest of the analysis pretty much worthless.

5. Even if the professor has his figures right, his reasoning is flawed: public debt is a gross figure whereas net assets is, well, a net figure. Comparing gross figures and net figures is like comparing durians and grapes; it simply does not make sense. Same goes for using Temasek’s portfolio value as comparison against the government’s net assets – again it’s comparing gross and net. Perhaps the professor might want to consider using Temasek’s shareholder equity instead for a net-to-net comparison.

================

You may like to look into these and possibly clarify them on TR Emeritus. Thanks!

Thanks for pointing this out. Here is the response I posted below:

Let me briefly respond to the 5 points raised by Morose:

1. “…the professor decided not to include cash of S$150b…”. I chose not to include this because there is an even larger offsetting liability for the Consolidated Fund. In 2012, the liability was $200 billion. While the balance sheet does not specifically say what the liability is for, these types of liabilities are normally for obligated spending in the future for any number of items such as pension obligation or contractually obligated spending that has not yet been spent. If Morose wishes to include cash as an asset, we should probably include the even larger Consolidated Fund liability.

2. “For some apparent reason, the professor decided to classify Development Fund (DF) and Government Securities Fund (GSF) as debt.” Well first of all the Singapore MOF balance lists two specific liability line items as Government Security Fund and Development Fund. Those are liabilities. That is the MOF classification not mine. Let me know if we need to review the concept of a liability. Second, Development Fund can be “loans…made to Singapore for the purposes of or properly allocable to the Development Fund…”. According to the MOF, Singapore has incurred liabilities with Development Funds. These need to be used for “capitalizable assets” which are then listed as assets on the other side of the balance sheet. If we ignore the fact that Development Funds are a specific line item under liabilities and the legal permission to incur liabilities, then yes, Morose is correct.

3. “$354 billion SGD in debt is different than the professors $457 billion.” Yes, because I include the Development Fund liability listed by the Singapore MOF. This appears to be a specific liability.

4. “Taking the above points into account, the government’s net asset for 31/3/12 should be S$765b – S$354b = S$411b as compared to the professor’s figure of S$122b”. Well since the above is wrong we don’t need to seriously address this. However, it should also be noted that as noted in the piece, I include the Development Fund liability as included by the MOF.

5. “..public debt is a gross figure whereas net assets is, well, a net figure. Comparing gross figures and net figures is like comparing durians and grapes; it simply does not make sense. Same goes for using Temasek’s portfolio value as comparison against the government’s net assets – again it’s comparing gross and net. Perhaps the professor might want to consider using Temasek’s shareholder equity instead for a net-to-net comparison.” Ok, I am more than will to use a commonly used comparison. If we compare Singapore’s debt to equity, a ratio of 4 to 1. To put this in perspective, Citigroup currently has a debt to equity ratio of 8.9 and Well Fargo has a debt to equity ratio of 8.0. This means that Singapore is significantly leveraged. Though we do not know the total number of investments as of March 31, 2013, given their total net assets of $122 billion SGD at March 31, 2012, it is unlikely this increased significantly through March 31, 2013.

Here is another reader’s comment in response to your comments addressing Moroose’s comments.

===================

Thomas Pain:

July 9, 2013 at 7:50 am (Quote)

@ Christopher Balding July 8 7.27

Quote

“This is incorrect. Look at the balance sheet. It clearly lists publicly listed investments. Now unless The MOF is holding on to another $600+ billion SGD in listed and unlisted financial assets unknown to the Singaporean public, they are consolidating Temasek and GIC.”

Response:

I am surprised at your reply. Why do you assume that the “publicly listed investments” are the stocks and shares of Temasek arising out of consolidation?

“Listed” and “Quoted” investments are any investments that are listed on any exchange for which there are buy/sell quotes and a public market. They include bonds and other non-equity securities.

Look at the liability of $358b listed under “Government Securities Fund”. Does this not look like the government debt in the form of outstanding T-Bills, SGS and SSGS? All these have to be repaid on their respective maturities.

Now look at the $116b and $289b in the assets under “Government Stocks” and “Other Investments – Quoted”. Does this not look like the matching cover in quantum (and I suspect in maturities) for the $358b government debt?

I maintain that the MOF statement of assets and liabilities DOES NOT include the portfolio of Temasek. At the most MOF might include the paid-up capital and loans to Temasek under “Other Investments – Unquoted” which looks like a catch-all classification.

I think I am right and you are wrong.

===================

You may like to clarify your view on this specific item.

Cheers!

Thanks for point this out to me. Here is my response below also posted at TRE:

@ Thomas Pain

1. “Listed” and “Quoted” investments are any investments that are listed on any exchange for which there are buy/sell quotes and a public market.” Thanks for that insight.

2. “Look at the liability of $358b listed under “Government Securities Fund”. Does this not look like the government debt in the form of outstanding T-Bills, SGS and SSGS? All these have to be repaid on their respective maturities.” Interesting. So debt has to be repaid on their respective maturities?

3. “Now look at the $116b and $289b in the assets under “Government Stocks” and “Other Investments – Quoted”. Does this not look like the matching cover in quantum (and I suspect in maturities) for the $358b government debt?” Thank you for making my point for me. Singapore has very little net assets because debt is being used to fuel gross asset growth.

4. “I maintain that the MOF statement of assets and liabilities DOES NOT include the portfolio of Temasek.” You have just created the worlds LARGEST sovereign wealth fund. Let’s assume that the MOF does NOT include Temasek or GIC, that means that the Singaporean MOF is now the worlds largest sovereign wealth fund and larger than GIC and Temasek COMBINED. According to you, somehow, the Singaporean MOF managed to become one of the worlds largest investors managing more than $600 billion SGD with no one noticing? That is what you are effectively claiming. You still want to believe that the Singapore MOF balance sheet does not include Temasek or GIC?

Thomas Pain responded to you in TR Emeritus as re-posted below.

=========================

@ Christopher Balding July 9 at 11.25

Thanks for your reply to my earlier comments. There is no necessity for your snide remarks.

I am beginning to understand why some of your articles make no sense. You are really not au fait with Singapore national accounts. You have the same access to public information that I have, but your interpretation of that information is incorrect.

Take the case of SG government debt. You think that SG government debt is the same like in other countries. You think that SG is a deadbeat country like Spain, Greece, et al

because SG has very little net assets to pay off the debt (your words). You are like someone who goes to the CIA World Factbook website and says, O my God, SG’s public debt at 111% of GDP is in the same band as Ireland (118%) and Iceland (119%). We must be in deep shit.

Countries run up debt for two main reasons. One, their budgets are in deficit, the revenues are insufficient to run the country, and two, to fund major infrastructure projects. Such borrowings go into the budgets and are spent on expenditures such as government salaries, welfare for single mothers, military adventures, build airports and so on. The money borrowed is spent, gone, finished. If the budgets remain in deficit for many years, the debt piles up and the debt service charge goes up until eventually the country is insolvent because they cannot repay the debts or pay the interest. This was what happened to Latin American countries in the past and would happen to Greece and Portugal if not for Deutschland uber Alles.

In SG’s case, we have had budget surpluses for decades (save for one or two years).The SG government received more revenuses than they needed for expenditures, the government had money coming out of its ears. Why then did they need to borrow and run up a public debt of $350 billion?

SG has a public debt mainly for 3 reasons:

1. T-Bills and SGS are money market instruments. There are hundreds of banks, financial institutions and investment houses that need to maintain liquid reserves and they subscribe or trade in them for this purpose. These total about $100 bn.

2. SG bonds, which are sovereign bonds, set yield benchmarks for the fixed income market..

3. Special SG Securities (SSGS) are issued only to CPF who hold them to maturity.

` Unlike other pension funds like EPF in Malaysia, Calpers in California or the Australian Supers who invest directly in various asset classes, our CPF is restricted by law to invest only in SSGS. The SG government takes the money from CPF and invest on their behalf. The SG government therefore acts like an investment agent for CPF.These total about $250 bn.

If you will look at any SG budget in the last 30 years, you will not find any receipts from borrowings in the Income column nor will you find any debt service charge. None of the borrowings flow into the budgets and none of it is spent. The total debt of $350 bn is parked with the MOF and invested.

That is why I said that the liability of $358 bn in the Government Securities Fund represents the proceeds of the public debt and the Listed and Quoted Investments are the matching cover for it. There can be no other explanation.

====================

Would you like to put forward any counter argument in response?

These issues have already been covered extensively and in detail but here is what I wrote.

I have already covered all of these issues extensively in my previous writings. So I won’t address them in detail. I will only say two things. First, I fully recognize that Singapore public debt is being invested. I have always noted this. However, just saying there are also investments does not make the debt any less real. It is still money that is owed. Second, given the amount of money that has been borrowed and the surpluses coupled with the returns claimed by GIC and Temasek should produce a vastly different amount of investments than what Singapore has. I agree that this money is listed as invested. However, based upon what they claimed to have earned and the amount of money invested, you cannot come close to reconciling that against what they claim to have.

The debt to gdp ration moved from 90% to 111% from 2007 to 2013. assuming gdp is not growing, that means the govt took up 21% of gdp more debt. if you compare this increase with the increase in asset of the govt over the same period, you will find that it is about the same. that means the investment is growing as fast.probably not growing.

Hi Prof, Few points. Thanks !

“More important however, is the evolution of Singaporean finances. The Singaporean government is in many instances, such as with SMRT, simply subsidizing the profits that accrue to Temasek via their portfolio holdings. Consequently, while Temasek makes money, the Singapore governments loses money, and the two numbers come close to balancing out.”

Bensktan: Could you please elaborate on your basis of govt subsidies? You ought to know very well some government companies or bodies are required sometimes to provide as low cost as possible public services to public at the expense of sheer profit motivations. Further, most Temasek companies pay good dividends, with Singtel earning 3-4B per year. Since temasek is making money why would govt need to subsidize? Also, any capital injection is capitalized and not a profit.

Good to be aware that many US and european social care funds are all in humongous deficits or under accrual to the extent these are potential crisis for social upheavals in not too distant future.

“The first basis for analysis is how an investor fared against the broader market. While Temasek is quite proud of its 8.86% total shareholder return between March 31 2012 and March 31 2013, this is less impressive than it appears. Over the same time period, the S&P 500 and FTSE returned 11.4% and 11.2% respectively. The Strait Times and the Hang Seng returned 9.9% and 8.5%. In other words, if Temasek only bought low cost exchange traded funds using the same geographic diversification strategy, they would have earned a slightly higher return of 9.2%.”

Bensktan: Any seasoned investors will regard temasek’s performance as within realms of reasonableness. Temasek invests in companies for their long term potentials. It is not Temasek’s investment strategies to move in an out of market daily or over short period of time in order to take profits on short term price fluctuations. Further, temasek holds majority stakes in many listed companies, just imaging the turbulences that would have been caused if temasek keeps investing and divesting it’s holdings. I believe all major SWF behave this wat too. Temasek companies market values fluctuate according to market forces prevailing in the sectors invested. This means the temasek companies return could be above or below the indices return over any period of time. For example, due to global economic situations, over the last few years the investments in resources are generally not doing very well while properties in some regions are. Also, it is common knowledge that every professionally managed fund have investment objectives, guides and risk profiles which govern return potentials. A low risk investment(such as government bonds) generally generate lower return. It is therefore not analogous to compare two funds with different investment profiles and objectives. Further, no fund managers have benefit of hindsights so it is useless for all the hindsights “could have’s and would have’s” higher returns.To get a realistic and non hindsight idea of how funds in the world performs, one could visit fund site such as

http://funds.ft.com/uk/

or many others.

Let me try and answer your questions.

1. Singapore subsidizes some of its portfolio companies. There is nothing wrong with earning a profit and there is nothing wrong with trying to provide low cost public services such as bus or subway transportation. What is wrong is providing subsidies to a company then having that company declare a profit making people think the company is making a lot of money. In the instance of SMRT, Singapore recently gave SMRT $1 billion SGD to buy buses and then SMRT declared about a $1 billion profit. That “profit” was due to the $1 billion provided by the Singapore government not due to the high quality management or savy investment skill of Temasek. The money is simply going in circles and creating misdirection. Does the distinction I am trying to clarify make sense?

2. I completely and entirely agree with your second point. That is why I wrote the following:

“As is repeatedly noted in finance research, there is no such thing as anyone who out performs the market for an extended period of time. In a way, a large institutional investor slightly underperforming the market by .4% is reassuring because it is what we expect in that they matched the market. This is the major concern about Temasek’s enormous claims about their long term returns: they do not match the underlying data of individual holdings or markets they were heavily invested in.”

It is reassuring that their returns are right in line with the market. For an investor of that size, that is what we would expect unless they are taking a lot of risk. I agree with you. That is why I say it is “reassuring” that the were right in line with the markets. It is not the 1 year investment return that is problematic. It is the claim by Temasek that their performance is more than twice as good as most every stock market in the world since 1974. That simply cannot be explained in anyway. Neither their underlying holdings or the markets they were heavily invested in returned the numbers they claim.

If there is anything that is unclear, please let me know.

Christopher

When the $1b is injected into SMRT, it would be in the form of capital injection and accounted as an increase in govt’s shareholding in SMRT. It is nonsensical to call it profit, nor would the current accounting standards treat it as profit.

A capital subsidy provides a free stream of cash flow to the company receiving the subsidy. Think of it this way. If a company likes SMRT receives a $1 billion subsidy to purchase buses, they have received a profit subsidy to the amount of their principal repayment over the life of the buses plus the interest cost. In other words, that is money they don’t have to pay back but instead can declare as profit. The subsidy is turned into a profit.

[Let me briefly respond to the 5 points raised by Morose:

1. “…the professor decided not to include cash of S$150b…”. I chose not to include this because there is an even larger offsetting liability for the Consolidated Fund. In 2012, the liability was $200 billion. While the balance sheet does not specifically say what the liability is for, these types of liabilities are normally for obligated spending in the future for any number of items such as pension obligation or contractually obligated spending that has not yet been spent. If Morose wishes to include cash as an asset, we should probably include the even larger Consolidated Fund liability.]

Bensktan:

Your explanation does not make sense.

The given B/S is already balanced. If you want to analyse the cash flow, cash is part of it.

As example, if all the investments were to be liquidated and converted to cash, so that investment asset value is left to be zero, would you be saying there were negative growth in net asset for the 300B plus increase in liabity?

If you would check with an accountant, Consolidated Fund is like Shareholder’s equity in a B/S, representing the net value left if all assets were liquidated into cash based on book values.

On the balance sheet, the line item for Consolidated Fund is listed under the “Liability” section. The Consolidated Fund is the general account of the Singaporean government out of which it pays its bills and into which it collects its revenue. This leads me to believe that the “cash” under the asset side is essentially the cash available to the government but the Consolidated Fund listed as a liability is committed expenditures. Many entities are required to list as liabilities future committed expenditures. For instance, pension funds are required to list future liabilities. Leases as generally listed as liabiliities. This leads me to believe there is a good reason this is listed as a liability here.

However, even if I am wrong and it as you propose the “shareholder equity” portion of the balance sheet, the creates enormous problems. This still leave a debt to equity ratio near 4. Furthermore, as the Singapore government has enjoyed public operational surpluses of more than $300 billion SGD. Consequently, for them to have just over $200 billion SGD is an enormous problem.

Just for your infor. There is no such thing as profit subsidy for SMRT as far I could see in SMRT’s financial statements. May be you could show me your sources.

The SMRT does not list a “profit” subsidy. However, because money is fungible any subsidy provided to the SMRT from the government essentially acts as a profit subsidy. When the government buys buses for SMRT, this allows SMRT to make more money because it does not have to pay for the principal and interest cost of the buses. Let’s take a simple example. Assume the buses have a 10 year life and principal and interest costs on $1 billion worth of buses in $150 million per year. (This is a very simple example). This is $150 million that SMRT gets to keep that it does not have to spend on repaying the costs of the buses it uses. Again, this is just an incredibly simple example for illustration purposes only. Hope that answers your question.

the guy who posed this question is kind of dumb, I mean, if smrt had been truely commercial, seeing the commercial potential of more buses, would have bought them themselves and earn the monies . but no, it depended the govt to give them the buses which will give them an increase a profit.

“the guy who posed this question is kind of dumb, I mean, if smrt had been truely commercial, seeing the commercial potential of more buses, would have bought them themselves and earn the monies .”

“but no, it depended the govt to give them the buses which will give them an increase a profit.”

Your intelligence certainly illuminates many.

I don’t know what you are trying to say here:

1. that the wealth of SMRT is its ability to charge whatever it wants and get the govt to pay for the buses/trains that it operates which it doesn’t maintain well (as evidenced day to day)

or

2. that you think my reasoning doesn’t make sense. honestly, that would tantamount to thinking that Samsung would let its cash generating machine of smartphone production crack by using lousy touch screens in the highly competitive smartphone market. If there is only one smart phone maker then Samsung can do whatever it wants but charge a premium like smrt using dysfunctional rails and trains to make monies out of Singaporeans.

3. you really think I am smart but I have to tell you many people are aware of this. Just join into any chat discussion on politics online.

To think SMRT didn’t get a free ride from free trains and buses is fucking stupid because transporting people is what makes it monies. Who would go to their tunnels to buy stuff when you have beautiful malls around competiting if it was not for the need of having to take the fuckup smrt train and the convenience of the stores along the way.

Until it could be ascertained which public finance organizations’ finances are consolidated in the assets and liabilities statement, you would just be making guesses about the figures. It is obvious that some organizations were left out. We could not even be sure if GIC’s is consolidated in the asset and liability statement. Special transfers of reserves amongst govt entities are allowed but are protected reserves not to be spent or used to cover losses.

The MAS has about $320B OFR

The Temasek portfolio was $215B

The HDB has a housing stock of about 900k units. Assuming the average value to be $400k per unit, the value for whole stock of HDB housing is around $360B.

The govt also owns many govt, ministry buildings and lands, schools, hospitals, military bases, planes, ships, subs, heli, structures, some with values determined while many do not.

Pingback: The Temasek Illusion | TravelSquare